Biographies of Cincinnati Modern Architects

- Modernnati

- Apr 6, 2022

- 6 min read

James Alexander

Architect Jim Alexander (1921-2007) graduated from the University of Cincinnati, interned in Raymond Loewy’s New York office, served in WW II, then returned to teach at UC from 1947-89. He designed over 100 houses, especially for wooded sites in Wyoming. He built his own house in four stages between 1949 and 1965, adding on as his family and income grew. What began as a modest, almost one-room plan became a multi-level complex with separate living, bedroom, and work areas. Alexander was instrumental in developing Congress Run, as the original landowner did not want to look from his hilltop and see other houses. Alexander’s low, modern designs fit in perfectly and several of his houses were built into this hillside.

1965 Christmas Card by James Alexander of his house in Wyoming, OH

The DAAP Library has 85 drawings of Alexander's work donated by the family after his death and a collection of his Christmas cards.

2002 thesis by Melissa Lauren Marty: JAMES M. ALEXANDER, JR., ARCHITECT AND DESIGNER: A STUDY OF HIS MODERN HOUSES IN WYOMING, OHIO

Robert A. Deshon

Robert Deshon (1915-2007) was born in Norwood, Ohio and graduated from the Ohio Mechanics Institute in 1934. Despite the Depression and meager resources, he entered the Architecture Program at the University of Cincinnati where he was a Rollman Scholar from 1937 to 1939. He graduated with a BA in Architecture in 1939 and a master's degree from MIT in 1940. In 1946 Deshon became a faculty member at UC and retired in 1980. His own house he designed for himself and his family is nestled in the woods and has a "floating on the site" quality.

Deshon Residence, 1950-1960. Cincinnati, OH. photographed in 2018.

Benjamin Dombar

Benjamin Dombar (1916 - 2006) arrived at Taliesin to study with Frank Lloyd Wright. Ben's older brother Abe was already there. The younger Dombar was 17 years old and had just graduated Hughes High School in Cincinnati. Ben Dombar had a more cheerful and extroverted personality than his brother and got along better at Taliesin, staying for seven years, until 1941. He was popular, based upon frequent mentions of him in memoirs by other Taliesin members. Ben worked to pay his way at the school and served a year in the Taliesin kitchen for a corresponding year of tuition. Ben became one of Wright’s favorite apprentices for construction supervision. Between 1935 and 1939, he assisted in building several Wright-designed houses, many of them “Usonians,” in the Madison, Wisconsin area. His assistance to Wright included work on the Johnson’s Wax Corporate Headquarters at Racine, WI; supervisory work at Taliesin East itself, the Bernard Schwartz House in Twin Rivers, WI (1939), and the Charles and Dorothy Manson House in Wausau, WI (c. 1938-40, at 1224 Highland Park Blvd.). Ben claimed that, between 1934-41, he participated in the design and construction of approximately 50 of Wright’s projects.

Ben Dombar’s daughter, Rockell D. Meese, donated his surviving architectural drawings and archival papers to the DAAP Library.

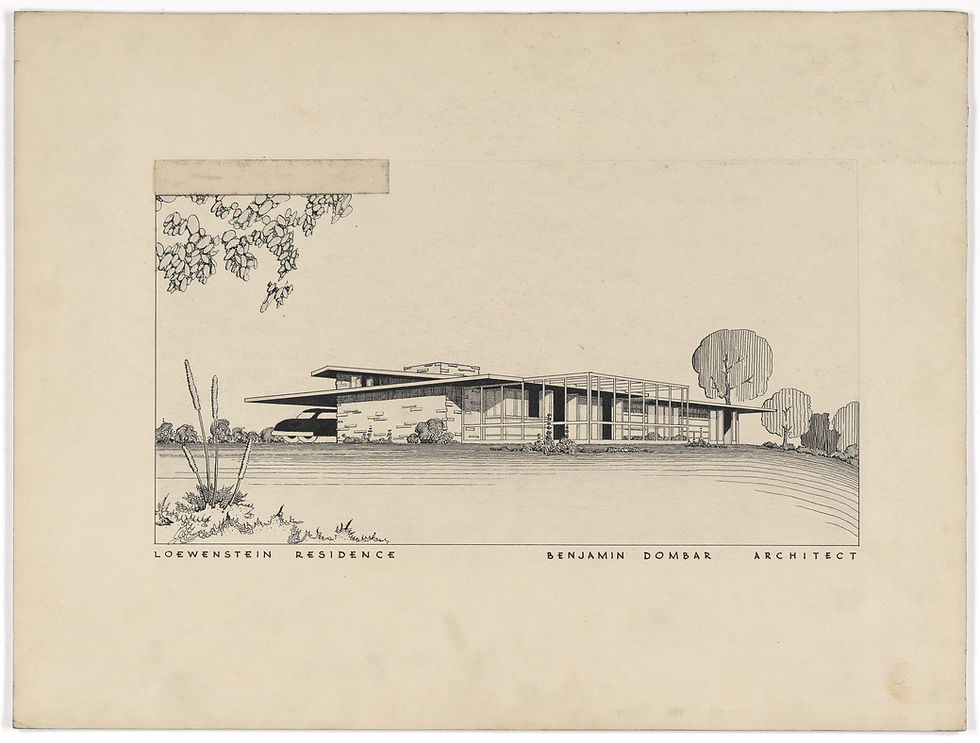

Loewenstein Residence, Perspective view Cincinnati, OH, by Benjamin Dombar

Abrom Dombar

Abe Dombar (1912 - 2009)early gravitated to art, taking drawing classes and doing illustrations for his school magazines both in the Avondale School and then, from 1926-30, at Hughes High School. Working part-time as a delivery boy in downtown Cincinnati, Abe became interested in design and buildings and entered the University of Cincinnati to study architecture, where he remained from 1930-32. In the UC Library he discovered books on Frank Lloyd Wright. One of his instructors, Professor Lane, encouraged his interest by presenting him a copy of Wright’s “Autobiography.” While at UC Abe worked as a cooperative education student in the display department at Shillito’s department store and in the office of Cincinnati architects Rapp and Mecham. Employed at the latter firm was architect Arthur J. Kelsey who also taught part-time at the University, was an early friend and Cincinnati enthusiast of Frank Lloyd Wright, and encouraged Abe's interest in Wright.

Carl Freund

Cincinnati Architect R. Carl Freund (1902-59) worked for the Cincinnati Park Board for three decades, from the 1930s-50s, and furnished the city’s parks with a delightful array of small buildings designed in Freund’s creative interpretation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Organic Modernism.

Born in Appleton, Wisconsin, slightly over 100 miles from Taliesin, Freund surely saw buildings by Wright, though Wright’s training of pupils began only in 1932, too late for Freund’s education. Freund studied architecture in the early 1920s at the University of Cincinnati—perhaps attracted by its developing co-operative education program that provided students with work experience in the offices of practicing architects. Freund worked in the offices of several Cincinnati architects, including John S. Adkins, Crowe and Shulte, Fechheimer and Ihorst, and Zettel and Rapp. Early in his career Freund specialized in religious buildings and schools, eventually establishing his own practice.

In 1930, with the Great Depression deepening and architectural work declining, Freund began contract work for the City of Cincinnati, soon becoming staff architect and building superintendent for the Board of Park Commissioners. Freund’s work corresponded with an influx of public funding and labor from Depression-era New Deal programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) that resulted in extensive construction in the city's public parks. Cincinnati's park system is one of the best in the United States, encompassing over 5,000 acres and including some of the city’s most varied and dramatic landscapes. Freund ultimately designed over three dozen park structures, ranging from shelter pavilions, to comfort stations, to lodges, and including the Park Board administration building in Eden Park.

Mt. Echo Open Shelter, Cincinnati, OH, by Carl Freund, 1940. Photographed by Alice Weston ca. 2000. From the University of Cincinnati Digital Collections & Repositories @UC Libraries

Woodward Garber

“Woodie” Garber came from a family of Cincinnati architects. He attended Cornell and worked briefly in New York City for Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and other firms before returning home in the early 1940s to become Cincinnati’s most extreme and experimental Modernist architect. An advocate of the International Style, Garber admired the works of LeCorbusier and interacted first-hand with German-immigrant originators of the movement including Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. Before the end of WW II, Garber captured national attention with his proposal for the Schenley Corporate Headquarters building on Lytle Park in downtown Cincinnati (1944-45). If built, it would have been the first fully modular, steel-frame, curtain-glass-wall skyscraper in America. Extensively published, this design placed him on the cutting edge, not just of Modernism in Cincinnati, but in the U.S. Its site, facing the Taft Museum, also placed him in opposition to the Tafts, Cincinnati’s most powerful family, and predicted his lifelong struggles to introduce his high-octane Modernism to his conservative hometown. Despite his controversial personality and being far ahead of his context, Garber found progressive patrons, such as Carl Vitz (head of the Cincinnati Public Library) and Mary E. Johntson (enthusiast of Modern Art and heir to the Procter fortune) who enabled him to create some extraordinary buildings, including the Cincinnati Public Library (1955, downtown) and Procter Hall (1968, at UC). He also designed eye-catching commercial buildings and factories, master plans for public schools, and a number of stunning glass residences, including his family’s home in Glendale. His buildings combined unorthodox planning and challenging experiments in structure and materials, including steel-shell, hyperbolic parabola roofs that could span over 60 feet with only three inches of thickness. Garber’s reward for being Cincinnati’s most unconventional Modernist was a lifetime of struggles and contentiousness that progressively took its toll on him and his family--as his daughter Elizabeth Garber powerfully documents in her 2018 book, IMPLOSION. During his lifetime, Garber achieved national celebrity while watching many of his Cincinnati buildings reviled, 0altered, and demolished, culminating in the 1991 implosion of the 26-story Sander Hall dormitory at UC, only 20 years after its completion, an event the architect insouciantly remarked from a boat in the Ohio River while drinking champagne. This destructive trend has continued after Garber’s death, resulting in the loss of some of Cincinnati’s most avant-garde Modernist buildings. One of Garber's greatest surviving legacies is the number of UC architecture students that he trained and employed in his office and who worshipped him and carried his fervor into future generations.

John deKoven Hill

John deKoven Hill (1920-96), a Frank Lloyd Wright pupil and Taliesin Fellow, designed a major house for J. Ralph Corbett and his wife Patricia in Cincinnati. Hill's family was from Cleveland and Chicago. He entered Taliesin in 1938 and remained for the rest of his life, except for a decade in New York City, from 1953-64, as an editor at House Beautiful magazine, an "assignment" given him by Wright. Hill was a rare, openly gay apprentice (others were more secretive about their sexuality) and though Wright certainly never discussed this, he recognized it at some intuitive level, ironically putting Hill in charge of his (Wright’s) clothes and closet and of arranging flowers in his personal rooms at Taliesin.

Hans Nuetzel

Hans Nuetzel (1921-2013), immigrated to Cincinnati in 1948. He worked with Carl Strauss as a project architect and later Cellarius and Hilmer, and then GBBN. He designed hundreds of houses in Cincinnati, many in Indian Hill. In 2014, John Nuetzel donated a collection of his father's drawings to the DAAP Library.

Finding Aid for Hans Nuetzel

Comments